AN/PRC-90 - Vietnam War era airman rescue set. AN/PRC-90-1

and AN/PRC-90-2 are improved, repairable versions. Operates on 243 and

282.8 MHz AM. The PRC-90 also included a beacon mode, and a tone

generator to allow the sending of Morse Code.

AN/PRC-90 - Vietnam War era airman rescue set. AN/PRC-90-1

and AN/PRC-90-2 are improved, repairable versions. Operates on 243 and

282.8 MHz AM. The PRC-90 also included a beacon mode, and a tone

generator to allow the sending of Morse Code.

AN/URC-10 - The RT-10 are subminiaturized, completely transistorized UHF radio sets. They consist of a crystal-controlled receiver-transmitter, a 16-v dry battery, and a power cable assembly. The unit operates on one channel in the 240-260 MHz band, usually 243 MHz. RT-60 and RT-60B1 were two frequency versions of the RT-10[8][20]

US National Personal Locator Beacon Program - (PLBs)

On 1 July, 2003 the FCC with the support of the USAF, USCG, NOAA, NASA, and FAA legalized the sale and use of 406 MHz Personal Locator Beacons (PLBS) in the United States. PLBs are portable radio distress signaling units that operate much the same as Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacons (for use on boats/vessels) or Emergency Locating Transmitters (for use on aircraft). These beacons are designed to be carried by an individual person instead of on a boat or aircraft. Unlike ELTs and some EPIRBs, PLBs can only be activated manually and operate exclusively on 406 MHz. All PLBs have a built-in, low-power homing beacon that transmits on 121.5 MHz. This allows rescue forces to home in on a beacon once the 406 MHz satellite system has gotten them "in the ballpark." Some newer PLBs also allow GPS data to be integrated into the distress signal.

This GPS-encoded position dramatically improves the location accuracy down to the 100-meter level (328 Feet) Once activated the beacons are picked up the COSPAS/SARSAT satellites system which relay distress signals to a network of ground stations and in the Us Inland Region ultimately to the U.S. Mission Control Center (USMCC) operated by NOAA in Suitland, Maryland. The USMCC processes the distress signal and alerts the appropriate search and rescue authorities (Rescue Coordination Centers). A critical portion of the system involves registration of the PLB by the Beacon Owner. This can now be accomplished very easily via NOAA's Online registration system.

This registration data is forwarded automatically to Rescue Coordination Centers and SAR first responders, providing important beacon owner and emergency contact data in the critical opening stages of a SAR case. Under the U.S National PLB Distribution System (Currently under development) PLB alerts will be sent directly to the state agency responsible for missing/distress persons within each state.

During the transition to the automated system the Air Force Rescue Coordination Center will notify the responsible state agency via voice/fax to begin SAR response per our established legal state SAR agreements and Memorandum of Understanding. et).

The AFRCC as the National PLB Program Manager is continuing to work with each state SAR coordinator to update their State SAR Agreement and Memorandum of Understanding to address the PLB alert receipt Issue. We will continue to update this are of our web site as the program develops.

U.S. Military survival radios

History

The use of radio to aid in rescuing survivors of accidents at sea came to the forefront after the sinking of the RMS Titanic in 1912. Lifeboats were equipped with spark gap transmitters such as the Marconi Type 241, c. 1920.[1][2] These operated using Morse code on 500 kHz, the international distress frequency at the time. This frequency had the advantage of long range due to ground-wave propagation and was constantly monitored by all large ships at sea after the Titanic's sinking. However, due to its wavelength of 600 meters, a long antenna was required to achieve good range. Long wires on the order of 1/4 wavelength held up by kites or balloons were often used. Spark-gap continued to be used in lifeboats long after the technology was banned for general communication.

The Gibson Girl

During World War II, Germany developed a hand-crank 500 kHz rescue radio, the "Notsender" (emergency transmitter) NS2. It used two vacuum tubes and was crystal-controlled. The radio case curved inward in the middle so that a user seated in an inflatable life boat could hold it stationary, between the thighs, while the generator handle was turned. The distress signal, in Morse code, was produced automatically as the crank handle was turned. An NS2 unit was captured by the British in 1941, who produced a copy, the Dinghy Transmitter T-1333. Britain gave a second captured unit to the United States, which produced its own copy, the SCR-578. United States Army Air Forces aircraft carried the SCR-578 on over-water operations. Nicknamed the Gibson Girl because of its hourglass shape, it was supplied with a fold-up metal frame box kite, and a balloon with a small hydrogen generator, for which the flying line was the aerial wire. Power was provided by a hand cranked generator. The transmitter component was the BC-778. The frequency was 500 kHz at 4.8 watts, giving it a range of 200 miles (300 km; 200 nmi). Keying could be automatic SOS, or manual. Crystals for frequency control were a scarce item for the U.S. during the war and the SCR-578 was not crystal-controlled.

A post-World War II version, the AN/CRT-3, which added a frequency in the 8 MHz range, was in use by ships and civil aircraft until the mid 1970s.[3]

VHF era

The use of aircraft for search and rescue in World War II brought line-of-sight VHF radios into use. The much shorter wavelengths of VHF allowed a simple dipole or whip antenna to be effective. Early devices included the British Walter, a compact single vacuum tube oscillator design operating at 177 MHz (1.7 meter wavelength), and the German Jäger (NS-4), a two-tube master oscillator power amplifier[4] design at 58.5 and, later, 42 MHz.[5] These were small enough to include in life rafts used on single-seat fighter aircraft.[citation needed]

Post-war designs included the British Search And Rescue And Homing beacon (SARAH) beacon made by Ultra Electronics, used in the location and recovery of astronaut Scott Carpenter after his Mercury space flight,[6] the U.S. AN/URC-4 and the Soviet R 855U. These operated on the aircraft emergency frequencies of 121.5 and 243 MHz (2.5 and 1.2 meter wavelengths).[citation needed]

Automated beacon systems

After a light plane with two U.S. congressmen on board went down in 1972 and could not be found,[7] the U.S. began requiring all aircraft to carry an Emergency Locator Transmitter (ELT) that would turn on automatically in the event of a crash. Initially these units sent beacon signals on the 121.5 MHz aircraft emergency frequency. These are being phased out in favor of ELTs that use a 406.025 MHz signal, which can be picked up by the Cospas-Sarsat international satellite system for search and rescue. Each 406 MHz beacon has a unique digital ID code. Users are required to register the code with the Cospas-Sarsat, allowing inquiries to be made when a distress signal is picked up. Some advanced models can transmit a location derived from an internal GPS or GLONASS receiver. Maritime practice has shifted from rescue radios on 500 kHz distress frequency (which is no longer officially monitored) to the Global Maritime Distress Safety System, which includes use of the Cospas-Sarsat system and other measures, including radar transponders and hand-held marine VHF radios.[citation needed]

There are many other types of emergency locator beacons that do not use the 406 MHz Cospas-Sarsat system, including man-overboard beacons that transmit Automatic identification system beacons and Avalanche transceivers.[citation needed]

Military organizations still issue pilots and other combat personnel individual survival radios, which have become increasingly sophisticated, with built-in Distance Measuring Equipment (DME), Global Positioning Satellite receivers, and satellite communication. In slang terms "PRC" radios were called a "prick" followed by the model number, "Prick-25," and "URC" radios were called an "erk." United States military survival radios include:

AN/CRC-7 - World War II era set, 140.58 MHz[8]

- AN/PRC-17

- AN/PRC-32 - Navy rescue sets, 243 MHz.[8]

- AN/PRC-49

- AN/PRC-63 - Smallest set built.[8]

- AN/URC-64 - (Air Force), 4 frequency rescue sets. Four crystal controlled channels (225-285 MHz)[8]

- AN/URC-68 - (Army), 4 frequency rescue sets.[8]

- AN/PRQ-7 Combat Survivor/Evader Locator (CSEL) combines selective availability GPS, UHF line of sight and UHF satellite

- communications along with a Sarsat beacon. It can send predefined messages digitally along with the user's location.[16][17] As of 2008, the PRQ-7 cost $7000 each, "batteries not included." A rechargeable lithium-ion battery pack cost $1600, while a non-rechargeable lithium-manganese dioxide unit cost $1520.[18] As of Oct, 2011 Boeing has delivered 50,000 PRQ-7s.[19]

- AN/URC-4 - 121.5 and 243 MHz[8]

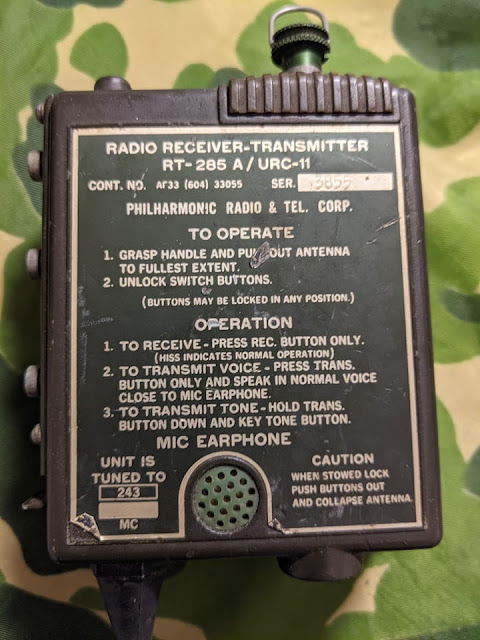

- AN/URC-10 - The RT-10 are subminiaturized, completely transistorized UHF radio sets. They consist of a crystal-controlled receiver-transmitter, a 16-v dry battery, and a power cable assembly. The unit operates on one channel in the 240-260 MHz band, usually 243 MHz. RT-60 and RT-60B1 were two frequency versions of the RT-10[8][20]

How a daring mission behind enemy lines turned into a disaster for the US's secretive Vietnam-era special operatons

Fifty-four years ago, a group of American and indigenous commandos fought for their very lives in a small, far away valley in one of the boldest special-operations missions of the Vietnam War.

Codenamed Oscar-8, the target was the forward headquarters of the North Vietnamese Army's 559th Transportation Group and its commander, Gen. Vo Bam, located alongside the Ho Chi Minh trail complex, which ran from North Vietnam to South Vietnam and passed through Laos and Cambodia.

US commanders had intelligence that Gen. Vo Nguyen Giap, North Vietnam's top general, was visiting the area. A plan was quickly hatched to kill or capture Giap. US commanders gave the mission to a highly secretive special-operations unit.

The secret warriors of a secret war

Military Assistance Command Vietnam-Studies and Observations Group (MACV-SOG) was a highly classified unit that conducted covert operations across the fence in Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, and North Vietnam.

Successive US administrations claimed American troops didn't operate outside of South Vietnam, so SOG was a tightly kept secret.

It was a standard operating procedure for any commandos who went across the border never to carry anything that could identify them as US service members. Their weapons didn't have serial numbers, and their uniforms didn't have names or ranks.

SOG was composed primarily of Green Berets, Navy SEALs, Reconnaissance Marines, and Air Commandos. They advised and led local forces, from South Vietnamese SEALs to Montagnard tribesmen who had lived there for hundreds of years.

During the Vietnam War, about 3.2 million service members deployed to Southeast Asia in combat or support roles. Of them, 20,000 were Green Berets, and out of those, only 2,000 served in SOG, with only 400 to 600 running recon and direct-action missions across the fence.

Although only the best served in SOG, luck and constant vigilance were necessary to survive. Many seasoned operators died because their luck ran out or because they became complacent.

A bold mission

Oscar-8 was a bowl-shaped area in Laos, only about 11 miles from the US Marine base at Khe Sahn in northern South Vietnam. The area was about 600 yards long and 2 miles wide and surrounded by thick jungle.

The mission was given to a "Hatchet Force," a company-size element that specialized in large-scale raids and ambushes. It was composed of a few Special Forces operators and several dozen local Nung mercenary troops, totaling about 100 commandos.

Several B-52 Stratofortress bombers would work the target before the SOG commandos landed.

The Hatchet Force's mission was to sweep the target area after the B-52 bombers had flattened it, do a battle damage assessment, kill any survivors and destroy any equipment, and capture or kill Giap. The plan was to insert at 7 a.m., one hour after the B-52 run, and be out by 3 p.m.

To support them, SOG headquarters put on standby several Air Force, Marine, and even Navy fixed- and rotary-wing squadrons.

All in all, there were three CH-46 Sea Knights helicopters to ferry in the Hatchet Force, four UH-1 Huey gunships for close air support, two A-1E Skyraider aircraft for close air support, four F-4C Phantom fighter jets for close air support, two H-34 choppers for combat search and rescue, and two forward observer aircraft to coordinate tactical air support.

Disaster at Oscar-8

As the sun began rising, nine B-52 bombers dropped 945 unguided high-explosive bombs, more than 236 tons of munitions, on the North Vietnamese headquarters and the adjoining positions.

Minutes after the B-52s finishing refurbishing the area, a forward air controller flying overhead spotted North Vietnamese troops coming out of the jungle and putting out the fires.

The enemy numbers continued to swell, and it quickly became clear to the seasoned SOG operators who were coordinating the fight from above that the North Vietnamese had largely managed to escape the onslaught from above.

Sgt. Maj. Billy Waugh, a legendary Special Forces operator and later a CIA paramilitary officer, radioed headquarters and advised aborting the inbound Hatchet Force, which was due to touch down 15 minutes after the last B-52 bomber had bombed the target. He was too late.

The first two CH-46 Sea Knight helicopters full of men were shot down, as were two UH-1 Huey gunships that were providing close air support. An H-34 chopper attempting a rescue was also shot down.

The SOG force was immediately pinned down and had to take shelter in the bomb craters that pockmarked the area. Only the Hatchet Force's firepower saved them from being overrun by the vastly numerically superior enemy.

Meanwhile, a pair of F-4 Phantom jets came in low to cover the survivors, but they also took heavy anti-aircraft fire, and one fighter was shot down, the pilot going down with his plane.

A

pair of A-1E Skyraiders then came in to provide close air support, but

they too received overwhelming anti-aircraft fire, and one of them

crashed.

There were about 45 SOG commandos taking cover inside two craters under heavy fire from the enemy on the ground. The American team leader requested napalm and cluster bombs to be dropped within 100 feet of their perimeter.

Meanwhile, another Hatchet Force was quickly assembled to act as a quick reaction force, while aircraft bound for North Vietnam on unrelated were redirected over Oscar-8 to keep the battered SOG commandos alive.

The North Vietnamese continued to fend off or shoot down any aircraft that tried to exfiltrate the SOG commandos, which prevented the quick-reaction force from inserting. But two days of concentrated air attacks against the NVA allowed the Hatchet Force to stay alive, and the commandos were eventually able to exfiltrate.

Twenty-three men from SOG and its supporting air units and about 50 of the indigenous fighters were wounded or killed, went missing, or were captured during the operation.

In addition, two CH-46 Sea Knight helicopters, one UH-1 gunship, one H-34 transport chopper, one F-4 Phantom jet, and one A-1E Skyraider were shot down.

During the fight, one seriously wounded American, Sgt. First Class Charles Wilklow, was captured by the North Vietnamese, who used him as bait for a rescue force for four days. Wilklow not only managed to survive his wounds but also escaped, getting picked up by a combat search and rescue chopper five days after the battle began.

Oscar-8 was a disaster for SOG. The Hatchet Force failed to achieve any of the mission's goals, and if it weren't for the sheer will and grit of the commandos and the aircrews, it would have been a lot worse.

Indeed, the operation highlights the dangers SOG operators faced on every mission. With the odds always against them, it's miraculous that their successes outweighed their failures.

Stavros Atlamazoglou is a defense journalist specializing in special operations, a Hellenic Army veteran (national service with the 575th Marine Battalion and Army HQ), and a Johns Hopkins University graduate.

RB-66C crew at Takhli in early 1966

(the RB-66C was later designated the EB-66C). The typical RB-66C crew consisted of the pilot/aircraft commander, navigator, flight engineer, and four electronic warfare officers (EWOs).

(U.S. Air Force photo)

No comments:

Post a Comment